The documentation of enslaved persons (EPs) is complicated by the common practice among American slaveholders (SHs) of referring to their EPs by an Anglicized given name only. In the rare documents where EPs are mentioned, as often as not they are described rather than named. Each new document a researcher discovers might refer to the same person by a different name or description.

One of the key values of documenting Beyond Kin relationships comes in comparing the EP names or descriptions in multiple sources. You will try to identify matches, slowly building a fuller picture of the individual EPs. And you will make note of the people who seem to have no match between sources. These raise questions about purchases and sales of EPs, births, deaths, and other possibilities.

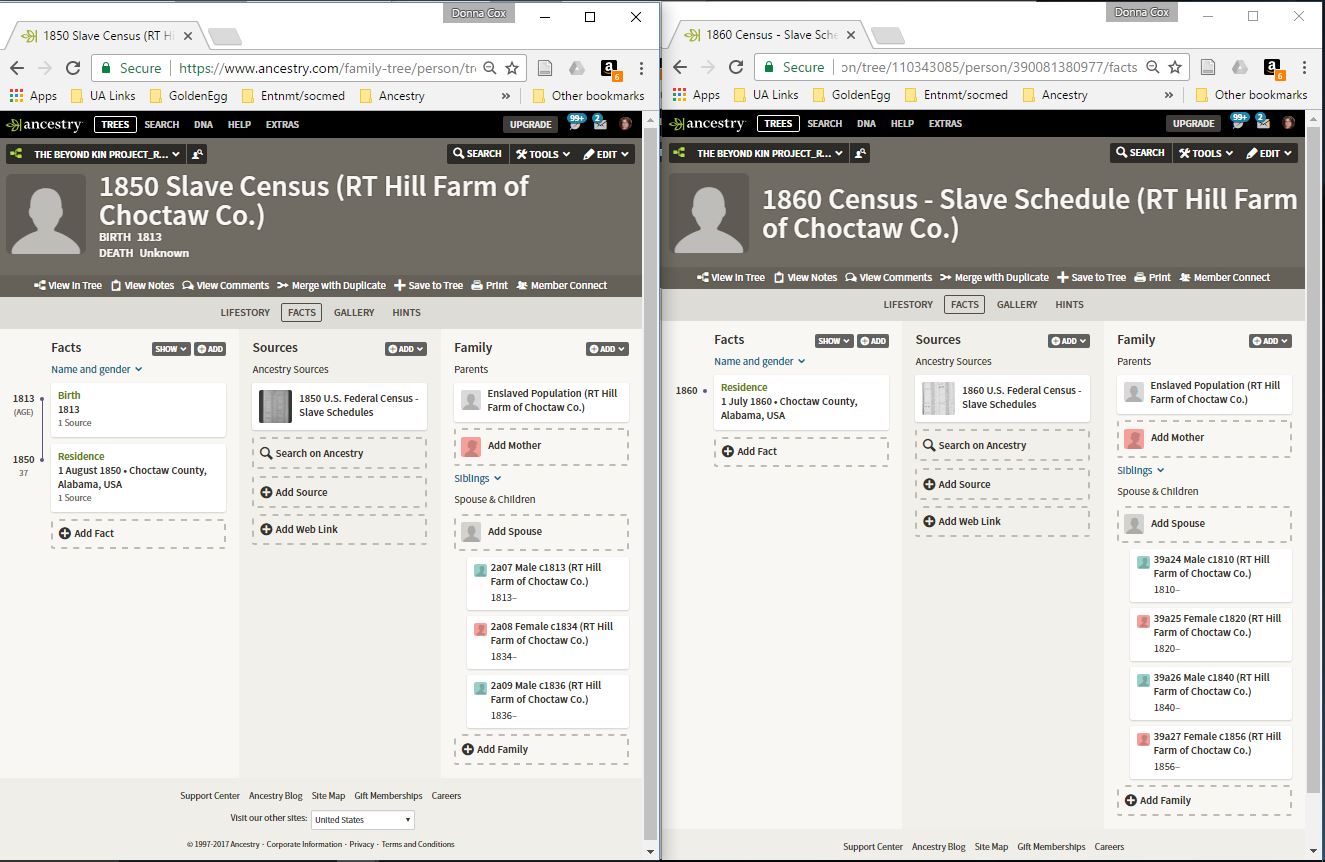

In the example below, two brother Source Children are displayed side by side, so that we can see how the EP group changed from 1850 to 1860 on the RT Hill Plantation in Choctaw County, Alabama. There were three EPs in 1850 and four in 1860. To look at the years of birth, it would seem that the 1860 census has an entirely different list. But it is more likely that the ages given in the censuses were guesses.

It is very possible that 2a07 Male c1813 from the 1850 census was also 39a24 Male c1810 from 1860. The young female, aged 4, in the 1860 census might have been a new purchase or inheritance. Or she could have been offspring of one or two of the other EPs. These questions begin to put a human story on the technical descriptions offered by the censuses and inspire other potential avenues to search.

To keep order in the growing documentation of an SH’s EPs, and to allow for meaningful comparison between them, a new Beyond Kin Source Child should be created for every new document that surfaces with names or descriptions of the EPs. As an EP changes SHs, being sold or inherited, a new Beyond Kin group will be created between the EP and his or her new SH. And you will make the first name the EP had an alternate name and rename them for the new institution. The Beyond Kin links, alternate names, and multiple foster parents create a bread-crumb trail for this EP back to every situation of enslavement.

Some lists of a SH’s EPs will be comprehensive lists, like censuses, by their nature indicating that the list contains every individual. Others may mention one or a few members of a larger EP population, as in a runaway advertisement or a sale or purchase. Some will name the people, others will describe them, and some will only mention them as “Jacob Mayberry’s negro man.” But every description, no matter how generic, matters and must be captured. You never know which tidbit of information will be the clue that ties EP records together — building a fuller picture of an EP’s life.

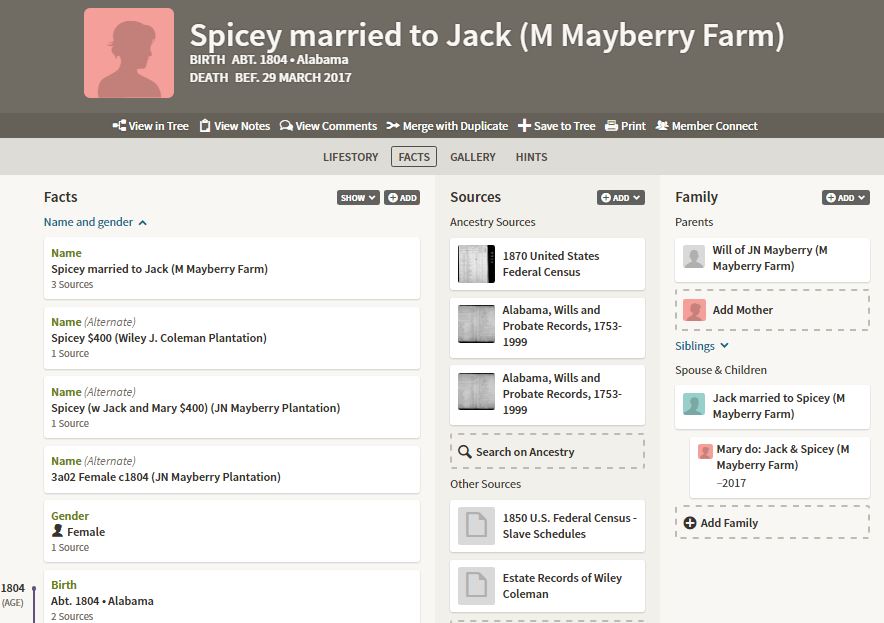

An EP will inevitably have multiple ancestry records until these variations can be intelligently merged. For example, the following enslaved woman, who I believe (but have not definitively proven) to have taken the post–Civil War name Spicey Davidson, was linked to three different SHs in four different source documents. She therefore had four different Ancestry.com identities with different names, until all the variations were matched and merged:

|

Multiple Identities for Spicey until Merged |

||

| Slaveholder | Beyond Kin Link |

Enslaved Person |

| Jacob N. Mayberry | EP/1850 Slave Census | 3a2 Female c1804 (JN Mayberry Plantation) |

| Jacob N. Mayberry | EP/Probate Inventory of Jacob Mayberry 1853 | Spicey with Jack and Mary $400 (JN Mayberry Plantation) |

| Mary Coleman Mayberry | EP/Will of Jacob Mayberry 1853 | Spicey married to Jack (M Mayberry Farm) |

| Wiley J. Coleman | EP/Probate Inventory of Wiley Coleman 1822 | Spicey $400 (Wiley J. Coleman Plantation) |

Merging duplicate records

Once a researcher has determined that the various EP records all belong to the same person, they can be merged, using the software’s merging capabilities. Assuming the merge tool is as robust as needed, the work done on the various records will combine as a set of details about a single EP. Merging can create a need for cleanup, so take the time to do that after you have merged multiple records. You’ll particularly want to check how it has arranged the multiple sets of parents.

A merged EP will also continue to appear in all the lists you have created under your Source Children, but their name will begin to be altered as you refine it. You will start to see sketchy names replaced with more descriptive ones and eventually with the EP’s chosen name after emancipation, if you are fortunate enough to make the connection. In the example here, you see a list that was created from an 1850 slave census for the JN Mayberry Plantation. The first three EPs continue to have the sketchy name from the census and are still tied to the JN Mayberry Plantation. We’ve been able to merge one of the original women in the census with a record that identified her as “Spicey married to Jack,” and by the new last name tells us she went to work on the M Mayberry Farm after her time at the JN Mayberry Plantation. We also see that we’ve successfully found the post-emancipation name for a former EP. Amanda Carnathan now carries her full name. If you view her record, you can see all the other names we gave her, on the path to finding the final name.

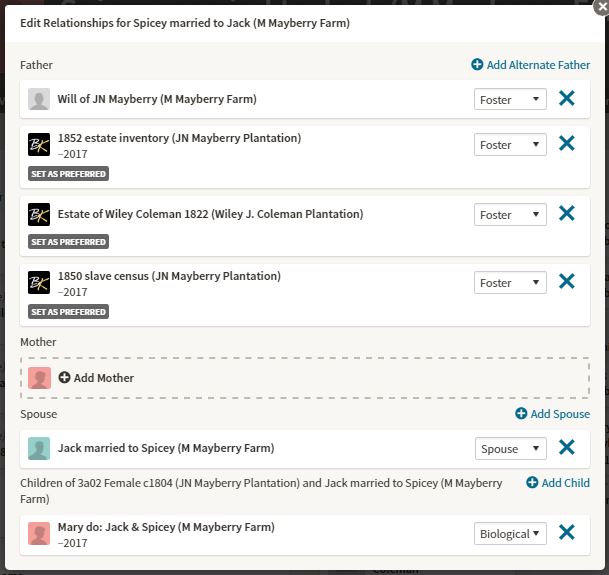

An audit trail of parents

The post-merge trail appears in two places. First, it will appear in alternate parents. Set them all up as foster relationships, if possible, making the record of the last enslavement situation the “preferred parent.” Here are the foster parents you see for the EP named Spicey we mentioned earlier. This is the “Edit Relationship” view in Ancestry.com after multiple records were merged:

An audit trail of names

The second aspect of the audit trail is in the collection of alternate names—each adding descriptive text to the EP’s record, and via the surname, giving the name of their place of enslavement at the time the description was created. One name will be chosen as “preferred,” but the other names should be preserved as alternates, creating a trail of the various descriptions of this person. Spicey’s record has these alternate names.

Real marriages of enslaved persons

One complication in using this workaround method lies in the fact that fellow EPs are set up as siblings. The software packages tend to resist the marriage of siblings, even when they have been set up as foster children in the same household. This is a software flaw that needs correction, given that siblings have married throughout time. But until they fix it, we will have to work around it.

The temporary workaround we found in Ancestry.com is to create a duplicate record for one of the two people who are marrying, using only the most basic information in this temporary duplicate. Marry the duplicate record to the enslaved partner, then merge the original record with its duplicate.

Be patient

One day, our software companies will create a module that makes this simpler. Meanwhile, put it into practice. And work through the issues that surface now and then. It will become easy before you know it.

Most importantly, you’ll find it worth every minute you invest when you start to see names replacing the nameless, families replacing pseudo-parents, and stories making them all real.

Sign up to receive notices of new developments in the project. We will not share your email address outside our team. If you have questions or would like to converse with others who are building Beyond Kin groups, join us at The Beyond Kin Project Forum on Facebook.