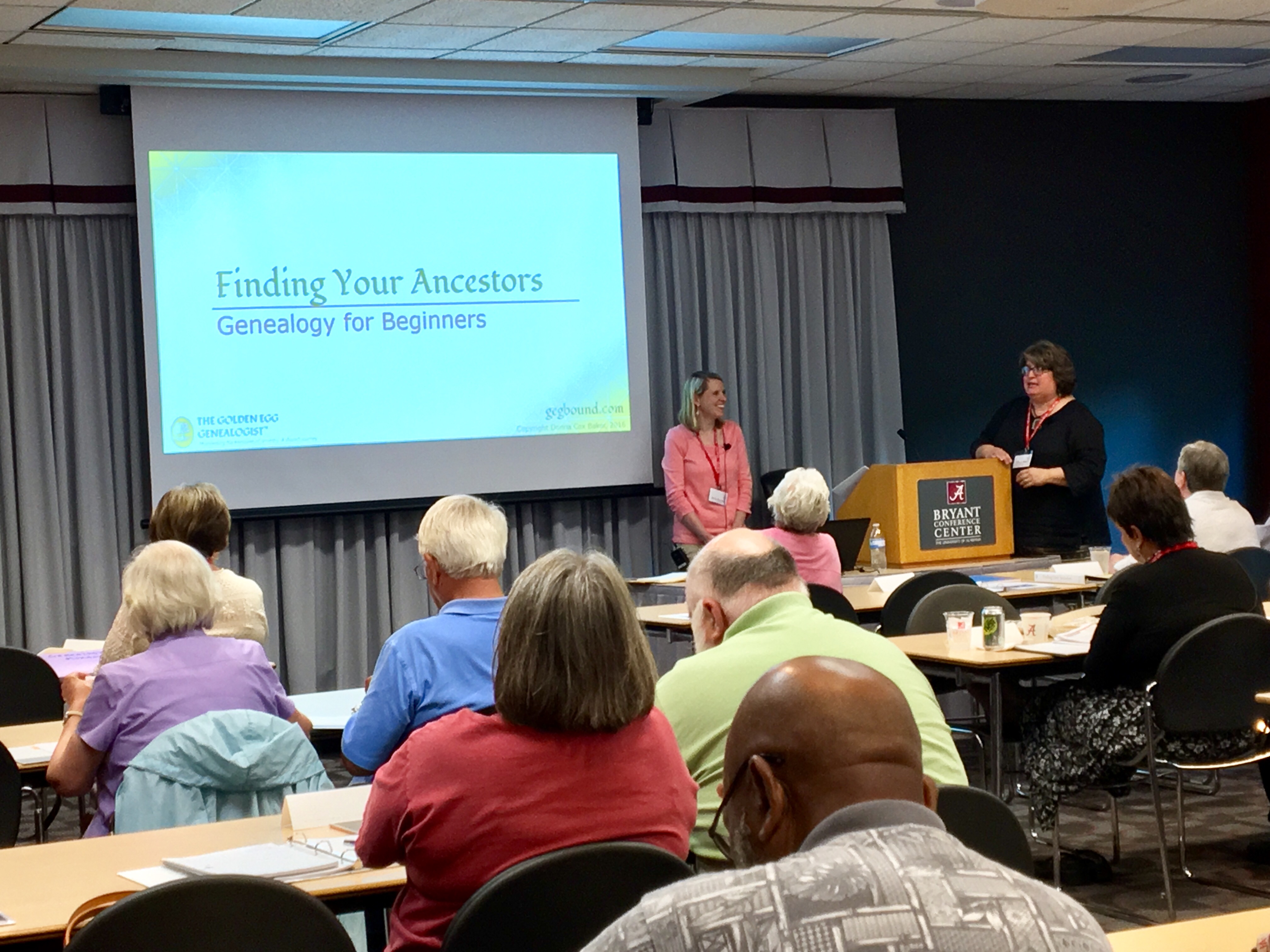

This idea originated one night in the fall of 2016, as Donna Baker was co-instructing a beginning genealogy class. A descendant of white southerners, Baker knew that the African American students in her class would face a much tougher challenge in tracing their family histories than she did. She had always felt compassion for this predicament, but it had never occurred to her that, in a very real sense, it was a predicament she shared and could do something about.

As her colleague, Dr. Susan Reynolds, began to teach the section on African American sources—displaying a bill of sale for a woman her own ancestor had purchased—it hit Baker for the first time: she wanted to document the enslaved persons (EPs) held by her own ancestors. She would be sorting through her family records anyway, every line and every page. It made sense that she should extract all she could find about their EPs.

But where should she begin? How could she record her findings? It kept her awake all night, eager to get started.

The next morning, her first call was to friend and colleague Frazine Taylor, who has been researching and teaching African American genealogy for more than 25 years and is highly respected for her skills. Baker, first and foremost, wanted Taylor’s blessing. Was she usurping a role that did not belong to her? Second, she needed to tap into her friend’s knowledge.

Taylor assured her that she had long recognized that African American genealogy requires a connection to the white families. She agreed wholeheartedly that genealogy could be revolutionized if the descendants of slaveholders (SHs) took up the charge of documenting all that could be found in their family records related to the EPs. She was on board and eagerly began to teach Baker how to do the research.

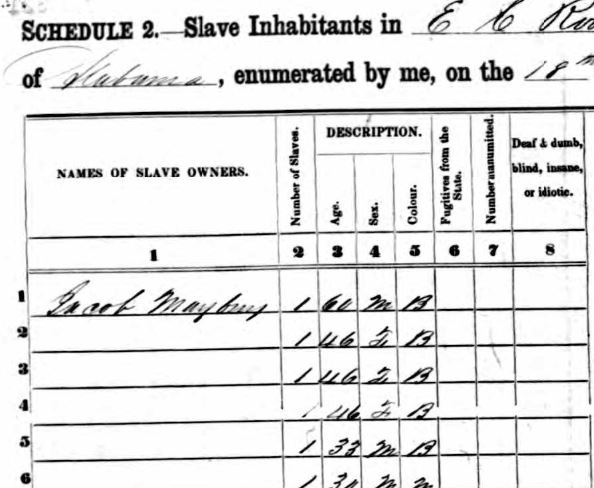

Recalling an ancestor rumored to have been escorted to the Civil War with an enslaved man, Baker decided to turn her attention to that family line, where she knew she would find at least one EP. Taylor sent her to the 1850 slave census where, to her shock, Baker discovered that her ancestor—Jacob Mayberry of Bibb County, Alabama—owned forty men, women, and children. They were nameless in this census, but there they were, and the real journey began.

Taylor helped her locate the property inventory in Mayberry’s probate papers and his bequests of EPs in his will, and the now-forty-two people began to have names and valuations. Her family story had, overnight, become a very complex one – an ideal prototype for the Beyond Kin concept that she and Taylor were shaping.

With Taylor’s help, Baker’s research had, within a few months, spread to plantations across four counties, where the various branches of her family lived. Their EPs were passed from fathers to children, inherited by marriage, bought and sold, were born and died.

In her family’s census records, wills, guardianship papers, deeds and other documents, Baker began to get to know a whole new group of people who had built her family’s experience of life. She realized what she now wants others to know: a genealogist cannot know her SH ancestors’ stories until she knows the EPs who supported and shaped their lives.

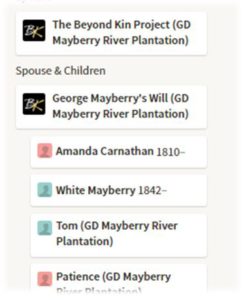

Given the very incomplete and often conflicting information available in most sources, along with the absence of surnames, documenting EPs proves challenging. Taylor and Baker recognized that the most effective research could be done with software that allows a link between the SH families and their EPs.

They began by creating a temporary solution using existing technology, as a short-term solution for those eager to get started. They now ask genealogical software and online tree vendors to modify their products to make the documentation of Beyond Kin simpler, more effective, transferable via GEDCOM, and a standard expectation in genealogical research.

They began by creating a temporary solution using existing technology, as a short-term solution for those eager to get started. They now ask genealogical software and online tree vendors to modify their products to make the documentation of Beyond Kin simpler, more effective, transferable via GEDCOM, and a standard expectation in genealogical research.

Sign up to receive notices of new developments in the project. We will not share your email address outside our team.